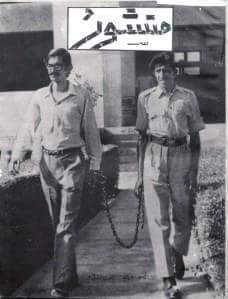

Dr Rasheed stood by his principles despite opposition from the government: the activist under arrest

“Students are not indulging in flattery when they claim to be the pulse of the nation; it is a fact borne out by historical experience.”

This was the opening line of the pamphlet NSF Calling penned in April 1967 by the young Rasheed Hassan Khan, general-secretary of the then nascent left-wing student organisation, the National Student Federation (NSF).

Principled, succinct, and insightful, Rasheed went on to establish NSF as the heart of left-wing student activism in Pakistan. It is on Rasheed Hassan Khan’s call that young women and men, myself included, entered NSF in what became a life-changing experience. Known by all as Rasheed, he passed away in his sleep on April 30, 2016 in Karachi; he was in his mid-70s.

An old associate recalls the legacy of an icon who helped shape progressive students politics

His association with NSF began soon after entering Dow Medical College in the early 1960s. He became a prominent figure due to his charismatic, selfless and disciplined personality. The primary attribute which made him a universally revered personality was the transformation of his life and ideas in concordance with the ideology and struggle of the oppressed class.

Rasheed was a Marxist-Leninist to the core. He was perhaps one of the very few people in the country who understood the essence of Marxism and hence had deep faith in the downtrodden. In his article, ‘The Bankruptcy of Idealist Political Discourse’, he talks about the division of society between two main classes, the oppressed and the oppressor, and the political, economic and social struggle between the two.

“Once the masses adopt the ideology of social change, it becomes a concrete force capable of changing the objective world,” he wrote. His belief in the eventual social change in the world despite the current retreat of the left is reflected by his statement: “Would there be no dawn if the rooster doesn’t crow?”

The student activist never formed a “splinter group” of NSF; in fact, the NSF he boldly led was NSF-Pakistan, the parent party whose discipline he followed like every common member. NSF stood for the political and cultural rights of provinces and protested against the one-unit policy.

While Rasheed’s understanding of class conflict was unparalleled, he also understood the inherent opportunism of the middle-class, whose role vacillates in the struggle between the oppressed and the oppressor. With the constant venom being spewed by the ruling elite through media, pulpits, social clubs, etc, it is but obvious that social pacifism, crass peace-mongering, opportunism, careerism and compromises with imperialism permeate into progressive organisations.

Dr Rasheed stood by the party and its central council in clearing the party of such adulteration.

NSF played a pivotal role in the mass movement of 1968. Z.A. Bhutto was invited to Dow Medical College to lead a pro-democracy protest staged by the students. The move was to counter the advance of right-wing political groups and to win political space for the Left.

Rasheed was later incarcerated after trial in a summary military court for protesting against the ban on student unions. His resolve, while under arrest, won him the admiration of fellow student leaders who were arrested at the same time. He refused to be bribed and was tortured for refusing to falsely incriminate Tariq Aziz, who had given a damaging interview against the jail administration for their treatment of prisoners.

Dr Rasheed and NSF also stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the workers of Karachi when the Bhutto government brutally suppressed their protest in Karachi. Although there were attempts to use NSF as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the government, the party corrected its line and stood firm.

Rasheed’s tireless leadership established NSF units in all four corners of the country. He took a ‘working holiday’ after his release from jail to visit units throughout the country. They went around educating students and masses that civilian rule is better than military rule, but real democracy is a long way ahead, and that people needed to remain vigilant.

Upon his return to Karachi, the police raided his home and DMC hostels; he subsequently went underground from ’73 until late ’78.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan brought up a new debate within the party. The party’s position was that the revolution couldn’t be brought from top to bottom by an external force. It has to have the wider participation of masses and the internal contradiction within the particular society has to reach a critical threshold. NSF did not see that happening in Afghanistan at that juncture.

Some elements were enamoured by the so-called ‘Afghanistan Revolution’ and supported the Soviet occupation. They were weeded out. It was Rasheed’s polemics that had brought clarity to NSF’s position on the Afghan question; he was later accused by the dissenting voices to have been ‘on the CIA’s payroll’ and ‘collaborating with Jihadists’.

One line of argument around Dr Rasheed is that perhaps NSF was ‘rigid’ or that in some instances at least, the party should have shown greater leniency. When I once raised this issue with Rasheed, his response was incisive:

“Tactics require flexibility to achieve your strategy. However, if the strategy itself is uncertain and shifting, we can never dream of success. The basic confusion in the minds of the critics of NSF is their inability to draw a line of distinction between flexibility and compromise. Thus, despite their criticism, their own practice is sterile and barren, resulting in nothing but empty words. Hence ‘rigidity’ in certain matters may be the prescription of choice.”

Dr Rasheed considered the work of a leftist organisation to be an ever going, almost endless endeavour. He once told me that our work is akin to that of Sisyphus, the mythological Greek king who was forced to carry a boulder uphill only to see it roll back. And hence the attempt was repeated over and over again.

The legacy of Rasheed, hence, has been his capability of transforming middle-class students, like this writer and thousands more, from apathetic individuals who read history as chance events, to men who see them from the point of view of class struggle.

Rest in peace my dear friend! You will be sorely missed.

Leave a Reply